Still Not on Board: The ASX’s Racial Diversity Deficit

By Afeeya Akhand, Head of Research and Policy, CiC

Despite Australia’s reputation as one of the most multicultural societies in the world, corporate leadership continues to lag far behind the country’s demographic reality. Nowhere is this gap more visible than on the boards of companies listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), with leadership overwhelmingly dominated by Anglo-Celtic males. To overcome the systemic underrepresentation of people of colour, tailored policy interventions, including a target for racially diverse leadership need to be implemented as a matter of priority.

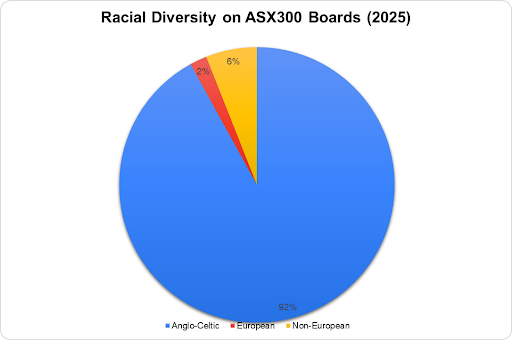

As highlighted by longitudinal research conducted by the executive search firm, Watermark, Anglo-Celtic Australians have consistently held at least 90 per cent of board positions on ASX300 boards since 2017 (see Figure 1). In 2025, that figure stood at 92% (see Figure 2). By contrast, Australians from non-European backgrounds consisted of merely 6% of board members, while those from continental European backgrounds accounted for only 2%.

Figure 1: Ethnic Origin of ASX300 Board Directors (2017-2025) (Source: Watermark)

Note: Watermark’s research did not include ethnic diversity data from 2023.

Figure 2: Racial Diversity on ASX300 Boards (2025) (Source: Watermark)

Note: Percentages rounded to the nearest whole number.

Such ASX leadership statistics are deeply out of step with Australia’s broader demographic reality and also with the level of racial diversity in other multicultural countries’ corporate boards. Asian-Australians, who are the largest racial group of non-European Australians in Australia, make up approximately 17% of the population. However, only 6% of ASX300 board members are from non-European backgrounds (including those with Asian backgrounds). Furthermore, when compared with the United Kingdom (UK), where 15% of company directors listed on the Financial Times Stock Exchange (FTSE) 250 came from ethnic minority backgrounds, the level of underrepresentation on ASX boards is even more shocking.

The business case for increased racial diversity on corporate boards is clear. As highlighted by the UK’s Parker Review of ethnic diversity, businesses need to recruit as “wide a talent pool as possible” including ethnic minorities in order to improve performance and market competitiveness. Likewise, increasing racial, cultural and linguistic diversity has a clear strategic dimension for many Australian companies engaging with foreign markets. Increasing the inclusion of Asian-Australians who have cross-cultural knowledge as well as linguistic and cultural competence based on their lived and professional expertise is a value-add for businesses as Australia’s top three trade partners are in Asia (China, Japan and South Korea respectively). In an increasingly competitive and geopolitically complex region, boards that lack this cultural competency lead to strategic blind spots that can directly affect long-term performance.

So why has progress been so slow?

One key reason is the narrow framing of diversity initiatives in Australia’s workplaces including ASX companies. Over the past decade, gender diversity has rightly been a major focus of reform, with the number of women on ASX300 boards increasing from 20% to 37% between 2016 and 2025. However, this focus on gender equality has often come at the expense of other forms of diversity with Watermark’s 2025 Diversity Index Report noting that “significant groups such as First Nations people, people from culturally diverse backgrounds, people with disabilities, and people from the LGBTQIA+ community continue to remain under-represented”.

Overt and structural racism in Australian workplaces plays a key role in perpetuating underrepresentation. Watermark’s 2017 Board Diversity Index report pointed to the phenomenon of boards selecting “People Just Like Me”, hence perpetuating the cycle of Anglo-Celtic male-dominated leadership.

In order to improve racial diversity on Australian boards, as a first step, improving the collation of diversity data is a key concern. Although organisations like Watermark actively collate and publish data on board diversity, such companies have noted the limitations of their respective methodologies. For Watermark, one key limitation is that much of its analysis does not always accurately capture cultural identity due to reliance on publicly available information about board directors such as place of birth, education and work history.

Rather than relying on publicly-available data and external inference, an improved data collation approach could involve direct engagement with ASX-listed companies to gather official diversity statistics. Quantitative data could also be complemented with qualitative insights through interviews with racially diverse individuals working within ASX companies. Such interviews would improve understanding about workplace expereinces beyond what can be extrapolated from statistics.

Importantly, the goal of increased racial diversity on ASX boards should not simply be to increase headline numbers. Focusing solely on representation risks creating a cycle of “board recycling”, where a small number of diverse individuals are appointed to multiple boards without broader systemic change. Diversity must be accompanied by genuine inclusion that ensures that racially diverse board members are not tokenistic appointments but active and influential participants in decision-making.

However, Australia does not need to reinvent the wheel to combat the racially homogeneous nature of its boards. Other countries offer applicable lessons, including the UK through its Parker Review which involved the introduction of recommendations for increased ethnic diversity in the FTSE 100 from 2017. One recommendation that has seen significant progress is the implementation of a voluntary target for UK boards to consist of at least one director from an ethnic minority background. In 2025, 95 FTSE 100 companies had met this target which is a significant improvement from 2016 where only 47 FTSE 100 companies had a director from a minority ethnic group. Due to the success of the UK’s approach, a similar voluntary racial diversity target for ASX companies could similarly be an effective tool in overcoming systemic underrepresentation.

Furthermore, any meaningful reform to diversity on boards must also adopt an intersectional approach that acknowledges and addresses overlapping forms of identity and marginalisation. Improving the inclusion of women of colour is one key concern. As noted by Diversity Council Australia, while women’s representation in ASX leadership reached record highs in 2023, culturally diverse women remained extremely rare. Socioeconomic background also deserves greater attention in intersectional initiatives. Diversity programs need to ensure that higher socio-economic groups from marginalised communities do not remain the primary beneficiary of diversity initiatives.

The fact that racial diversity on ASX boards has been measured and discussed in recent years by organisations including Watermark and Diversity Council Australia marks an important shift. But the collation of more comprehensive data on this topic alone is not enough. To address the systemic underrepresentation of racially diverse Australians in corporate leadership, ASX companies must move beyond passive commitments and adopt targeted strategies including the implementation of voluntary racial diversity targets. Only then will boardrooms begin to reflect the diversity of the society, and the markets they are meant to serve.